In the world of finance, few phenomena evoke as much fear, uncertainty, and dread as the bear market. These downturns can wreak havoc on portfolios, shatter investor confidence, and even destabilize economies. Yet, like any natural force, understanding bear markets can empower investors to weather the storm and emerge stronger on the other side. This article aims to explain the nature of bear markets, their causes, historical examples, and most importantly, strategies for navigating these turbulent times.

The Bear Market Definition

Before we can understand bear markets, it’s crucial to define them. In simplest terms, a bear market refers to a prolonged period of declining stock market prices, typically marked by a 20% or greater decline from recent highs. Unlike the fleeting volatility of corrections, which involve declines of 10% or more but often resolve quickly, bear markets are more sustained and severe.

Generally, a bear market occurs when a broad market index falls by 20% or more over at least a two-month period.

Investor.gov

Bear markets are characterized by pervasive pessimism, investor anxiety, and a general sense of gloom. Economic indicators such as rising unemployment, slowing GDP growth, and declining corporate profits often accompany these downturns, exacerbating the negative sentiment.

Causes and Catalysts

Understanding the causes and catalysts of bear markets is essential for any investor seeking to anticipate or navigate them. While each bear market has its own unique triggers, several common factors tend to play a role:

Economic Downturns

Economic recessions, characterized by contracting GDP, rising unemployment, and weakening consumer confidence, often coincide with bear markets. These downturns can stem from a variety of factors, including excessive debt, inflationary pressures, or external shocks such as geopolitical conflicts or natural disasters.

Asset Bubbles

Periods of irrational exuberance can lead to the formation of asset bubbles, where prices of stocks, real estate, or other assets become detached from their underlying fundamentals. When these bubbles inevitably burst, as they did during the dot-com crash of 2000 or the housing market collapse of 2008, bear markets often follow.

Geopolitical Uncertainty

Wars, trade disputes, political instability, and other geopolitical events can roil financial markets and trigger bearish sentiment. Investors tend to flee to safe-haven assets during times of geopolitical turmoil, driving down stock prices in the process.

Monetary Policy

Central bank actions, particularly interest rate hikes aimed at curbing inflation or cooling overheated markets, can also spark bear markets. Tightening monetary policy can increase borrowing costs for businesses and consumers, slowing economic growth and dampening corporate profits.

Technological Disruption

Advances in technology can disrupt entire industries, rendering some companies obsolete while creating opportunities for others. The transition from traditional brick-and-mortar retail to e-commerce, for example, has led to the demise of numerous traditional retailers and contributed to market downturns.

Bear Markets and Recessions

While it’s common for bear markets to coincide with economic recessions, the two are not synonymous. A recession is typically defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, indicating a broad-based contraction in economic activity. Bear markets, on the other hand, are purely financial phenomena driven by declining stock prices.

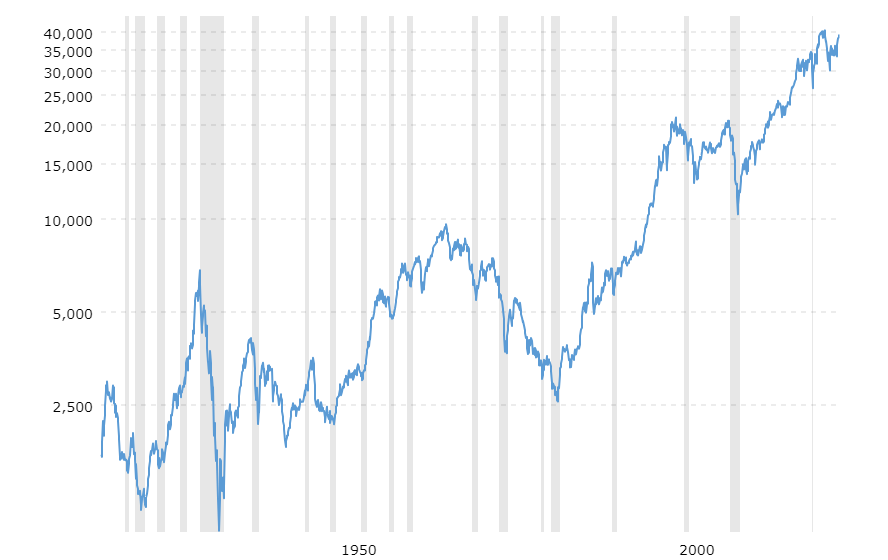

100 years of Dow Jones Industrial Average (logarithmic and inflation adjusted). As you can see on the chart, not all bear markets went along with recessions (grey zones). Source: macrotrends.net

While economic recessions often contribute to bear markets by undermining corporate profits and investor confidence, not all bear markets are accompanied by recessions. For example, the bear market that occurred in 1987, known as Black Monday, was relatively brief and intense but did not lead to a recession. Similarly, the bear market triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was severe but was followed by a sharp economic rebound rather than a prolonged recession.

History of the Bear Markets

Throughout history, bear markets have been a recurring feature of financial markets. While each bear market is unique, several notable examples offer valuable lessons for investors.

The Great Depression (1929-1932)

Perhaps the most infamous bear market in history, the Great Depression saw U.S. stocks lose nearly 90% of their value from peak to trough. The crash was precipitated by the bursting of the speculative bubble in the stock market, exacerbated by a banking crisis and a series of protectionist trade policies.

Investors avidly trade dot-com stocks from internet startups, until the bubble burst in 2000.

Goldman Sachs

The Dot-Com Crash (2000-2002)

Fueled by the rapid rise of internet-related stocks, the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, leading to a prolonged bear market. Many tech companies with sky-high valuations saw their stock prices plummet as investors reassessed their growth prospects. The Nasdaq Composite Index, heavy with technology stocks, lost over 75% of its value during this period.

The Global Financial Crisis (2007-2009)

The collapse of the U.S. housing market, fueled by subprime mortgage lending and complex financial instruments, triggered a worldwide financial meltdown. Stock markets around the globe tumbled as banks failed, credit markets froze, and economies entered recession. The S&P 500 index lost more than 50% of its value during this bear market.

The COVID-19 Pandemic (2020)

The rapid spread of the novel coronavirus and subsequent lockdown measures sent shockwaves through financial markets in early 2020. Fears of a global recession, coupled with uncertainty surrounding the pandemic’s impact on businesses and supply chains, led to a swift and severe bear market. Major stock indices experienced their fastest descent into bear territory in history, although unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus measures helped fuel a rapid recovery.

Other examples of the Bear Markets

| Bear Market Period | Duration | Total S&P 500 Decline |

| Aug 1956 to Oct 1957 | 14 months | -22% |

| Dec 1961 to Jun 1962 | 6 months | -28% |

| Feb 1966 to Oct 1966 | 8 months | -22% |

| Dec 1968 to May 1970 | 17 months | -36% |

| Jan 1973 to Oct 1974 | 21 months | -48% |

| Nov 1980 to Aug 1982 | 21 months | -27% |

| Aug 1987 to Dec 1987 | 4 months | -34% |

| Jul 1990 to Oct 1990 | 3 months | -20% |

| Mar 2000 to Oct 2002 | 31 months | -49% |

| Oct 2007 to Mar 2009 | 17 months | -56% |

| Feb 2020 to Mar 2020 | 1 month | -34% |

| Jan 2022 to Oct 2022 | 10 months | -25% |

S&P 500 Bear Markets (1956-2024). Source: Forbes, LPL Research and CFRA.

Stages a Bear Market

Bear markets, like a play unfolding, usually follow distinct stages, each with its own characteristics:

- Early Stage: The initial decline is often moderate, and some investors may view it as a buying opportunity. However, negative news and economic data can quickly escalate the decline. Picture the first snowflakes falling – a seemingly harmless phenomenon, but it can mark the beginning of a harsh winter.

- Downturn: As the decline deepens, pessimism sets in. Selling intensifies, and volatility increases. Corporate earnings reports and economic data become closely scrutinized for any sign of recovery. Imagine a blizzard gathering momentum – the market conditions worsen rapidly.

- Capitulation: This stage is like a dam breaking. Panic selling erupts as investors lose faith in the market and scramble to exit their positions. Prices can plummet in a short period, creating a chaotic atmosphere.

- Bottoming Out: Eventually, the selling pressure subsides, and the market reaches a low point. Investor sentiment may remain cautious, but bargain hunters may start to emerge. Imagine a winter day with no further snowfall – the storm has passed, but the landscape remains icy.

- Recovery: The market gradually starts to thaw, with prices rising slowly. Investor confidence begins to return, but the path to a full recovery can be long and uneven. Picture the spring thaw – the chill gradually recedes, but it takes time for the ground to fully recover.

Survival Strategies

While bear markets can be daunting, they also present opportunities for savvy investors to deploy strategies aimed at minimizing losses and even capitalizing on downturns. Here are some specific strategies to consider.

Diversification

One of the most effective ways to mitigate the impact of bear markets is through a well-diversified portfolio. By spreading investments across different asset classes, sectors, and geographic regions, investors can reduce their exposure to any single source of risk. This means not only diversifying across stocks but also considering investments in bonds, real estate, commodities, and other asset classes.

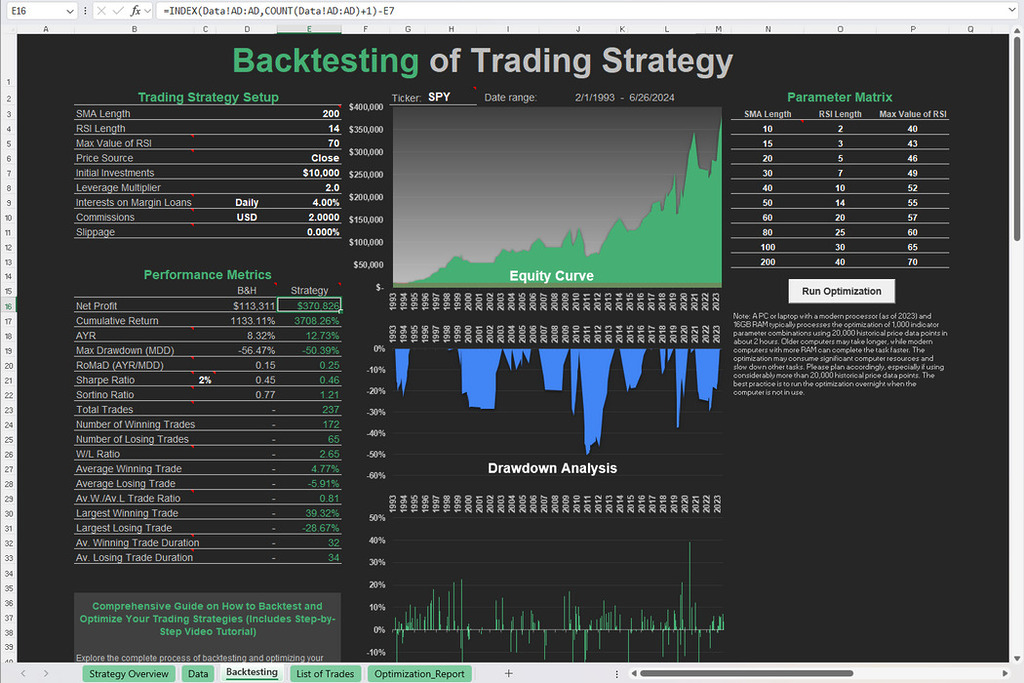

Free Backtesting Spreadsheet

Asset Allocation

Allocating a portion of the portfolio to defensive assets such as bonds, cash, or gold can provide stability and offset losses incurred by equity holdings. Rebalancing the portfolio periodically to maintain the desired asset allocation is also important, as market fluctuations may cause the original allocation to drift over time.

Value Investing

Bear markets often present opportunities to acquire quality assets at discounted prices. Value investors, following the principles of Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett, seek out undervalued stocks with strong fundamentals and long-term growth potential. Patience and discipline are key, as it may take time for the market to recognize the intrinsic value of these investments. Conducting thorough fundamental analysis and focusing on companies with sustainable competitive advantages can help identify attractive investment opportunities.

Dividend Investing

Companies that continue to pay dividends during bear markets can provide a source of income and stability for investors. Dividend-paying stocks with a history of consistent payouts and sustainable dividends are particularly attractive during periods of market volatility. Reinvesting dividends can also help compound returns over time, providing a valuable source of long-term wealth accumulation.

Tactical Asset Allocation

In addition to maintaining a long-term strategic asset allocation, investors can employ tactical asset allocation strategies to capitalize on short-term market trends. This may involve increasing exposure to defensive sectors or asset classes during bear markets and rotating back into riskier assets as market conditions improve. Market timing can be challenging, so it’s essential to base tactical allocation decisions on thorough analysis and research rather than short-term speculation.

Risk Management

Implementing stop-loss orders can help protect against downside risk and preserve capital during bear markets. It may not eliminate losses entirely, but can help mitigate the impact of market downturns and prevent emotional decision-making.

Short Selling

Short selling involves borrowing shares of a stock from a broker and selling them on the market with the expectation that the stock’s price will decline. This strategy can be risky, as it exposes investors to potentially unlimited losses if the stock price rises instead of falls. However, short selling can also provide an opportunity to profit from declining stock prices during bear markets, particularly for experienced investors who can accurately identify overvalued stocks.

Hedging

Hedging involves taking offsetting positions to protect against potential losses in a portfolio. This can be achieved through various instruments such as options, futures, or inverse ETFs. For example, purchasing put options on individual stocks or stock indices can provide downside protection during bear markets, as the value of the put options increases as the underlying stock or index declines in price. Similarly, investing in inverse ETFs or short-selling futures contracts can allow investors to profit from market downturns while hedging against potential losses in their long positions.

Maintain Perspective

Finally, it’s essential for investors to maintain a long-term perspective and avoid making impulsive decisions based on short-term market movements. Bear markets, while painful in the moment, are often followed by periods of recovery and growth. Staying disciplined and sticking to a well-thought-out investment strategy can ultimately lead to better outcomes over the long term. Remembering that market downturns are a normal part of the investment cycle and focusing on long-term goals can help investors navigate the uncertainty of bear markets with confidence and resilience.

Final Thoughts

Bear markets are an inevitable part of investing, characterized by declining stock prices, economic uncertainty, and investor pessimism. While navigating these downturns can be challenging, understanding the underlying causes, historical precedents, and effective strategies for managing risk can empower investors to weather the storm and emerge stronger on the other side. By maintaining a diversified portfolio, adhering to a disciplined investment approach, and staying focused on long-term goals, investors can navigate the wilderness of bear markets with confidence and resilience.

Share on Social Media: