Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from the performance of an underlying asset, index, or variable. This underlying asset could be anything from stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates, or even other derivatives. These instruments serve various purposes, including risk management, speculation, and investment. They have gained immense popularity in financial markets due to their ability to offer exposure to various assets without the need for direct ownership.

Characteristics of Derivatives

Derivatives exhibit several key characteristics. Firstly, they enable leveraged investment, allowing investors to control a large position with a relatively small amount of capital, which amplifies both potential returns and risks. Secondly, derivatives offer flexibility, providing a wide range of strategies for investors, including speculation, hedging, arbitrage, and portfolio diversification. Finally, derivatives contribute to market efficiency by providing mechanisms for price discovery and risk transfer, thus enhancing overall market dynamics and liquidity.

Types of Derivatives

Derivatives encompass a diverse array of financial instruments, each designed to serve specific purposes and cater to distinct market needs. Here’s an exploration of the main types of derivatives.

Futures contracts are standardized agreements between two parties to buy or sell an underlying asset at a predetermined price (the futures price) on a specified future date.

#1. Futures

Futures contracts are standardized agreements between two parties to buy or sell an underlying asset at a predetermined price (the futures price) on a specified future date. These contracts are traded on regulated exchanges, providing liquidity and transparency to market participants. Futures contracts are extensively used for hedging and speculation across various asset classes, including commodities, currencies, stock indices (indices futures), and interest rates.

Hedging: Hedgers, such as farmers, miners, and manufacturers, use futures contracts to mitigate the risk of adverse price movements in the underlying asset. By locking in prices through futures contracts, hedgers protect themselves from potential losses resulting from unfavorable market conditions.

Speculation: Speculators seek to profit from anticipated price movements in the underlying asset by taking positions in futures contracts. Speculative trading in futures allows investors to capitalize on both rising (long positions) and falling (short positions) market trends, amplifying potential returns but also increasing the level of risk.

Margin Trading: Futures trading typically involves the use of leverage, enabling investors to control a larger position with a relatively small initial investment (margin). While leverage can amplify profits, it also magnifies losses, making futures trading a high-risk endeavor for inexperienced traders.

Rolling Contracts: Futures contracts have finite expiration dates, after which they are settled or rolled over into new contracts. Roll-over strategies involve closing out expiring positions and simultaneously opening new positions in subsequent contract months to maintain exposure to the underlying asset.

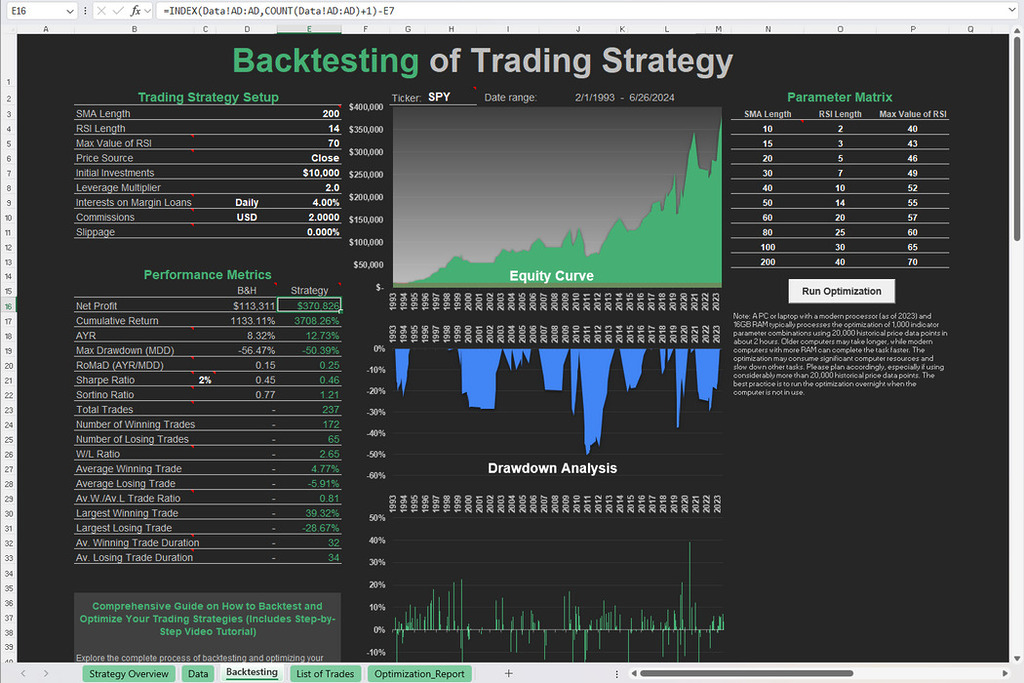

Free Backtesting Spreadsheet

Example of Futures Trade

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario where an investor anticipates a bullish trend in the price of crude oil due to geopolitical tensions in oil-producing regions. The investor decides to speculate on the price of crude oil futures contracts traded on a commodity exchange.

The investor conducts thorough research and analysis of various factors influencing the crude oil market, including supply and demand dynamics, geopolitical events, macroeconomic indicators, and technical analysis of price charts. Based on their analysis, the investor believes that escalating tensions in oil-producing regions will lead to a spike in crude oil prices in the coming months.

Then the investor chooses to take a long position in crude oil futures contracts, betting on a price increase and decides to trade a standard crude oil futures contract, which typically represents 1,000 barrels of oil.

The investor reviews the contract specifications for crude oil futures contracts, including the contract size, tick size, expiration date, and margin requirements. Suppose the current price of crude oil futures is $60 per barrel, and the investor expects the price to rise to $70 per barrel within three months.

Assuming a margin requirement of 5%, the investor calculates the initial margin required to enter the futures position. With a contract size of 1,000 barrels and a futures price of $60 per barrel, the total contract value is $60,000. The initial margin required is 5% of the contract value, which amounts to $3,000. Since futures trading involves leverage, the investor only needs to deposit the initial margin amount of $3,000 to control the entire contract value of $60,000. This leverage amplifies the investor’s potential returns but also increases the level of risk.

Next, the investor places a buy order for one crude oil futures contract at the current market price of $60 per barrel. After entering the futures position, the investor closely monitors market developments, news events, and price movements in the crude oil market. They set profit targets and stop-loss levels to manage risk and protect their investment.

Positive Scenario: As the anticipated price increase materializes and the price of crude oil futures rises to $70 per barrel, the investor decides to close their long position to realize profits. They place a sell order for the futures contract at the prevailing market price, locking in their gains.

Negative Scenario: However, if geopolitical tensions ease, leading to an unexpected increase in oil supply or a decrease in demand, the price of crude oil may decline instead of rising as anticipated. In this scenario, the investor’s long futures position would incur losses as the contract’s value decreases. If the price of crude oil declines significantly, the value of the investor’s futures position may fall below the maintenance margin level set by the exchange. In this case, the investor may receive a margin call from their broker, requiring them to deposit additional funds to meet the margin requirement or liquidate a portion of their position to cover the shortfall.

In the event of a margin call, the investor may choose to deposit additional funds to maintain their futures position or close out the position to prevent further losses. By implementing risk management strategies and closely monitoring margin requirements, investors can mitigate the risk of margin calls and protect their capital.

Options contracts grant the holder the right, but not the obligation, to buy (call option) or sell (put option) an underlying asset at a predetermined price within a specified period.

#2. Options

Options contracts grant the holder the right, but not the obligation, to buy (call option) or sell (put option) an underlying asset at a predetermined price (the strike price) within a specified period (until expiration). Options are versatile instruments used for hedging, speculation, income generation, and risk management in financial markets.

Types of Options

- Call Options: Call options give the holder the right to buy the underlying asset at the strike price before or at expiration. Call buyers profit from rising asset prices, while call sellers (writers) collect premiums in exchange for assuming the obligation to sell the asset if exercised.

- Put Options: Put options provide the holder the right to sell the underlying asset at the strike price before or at expiration. Put buyers profit from falling asset prices, while put sellers collect premiums and may be obligated to buy the asset if exercised.

Example of Option Trade

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario where an investor seeks to capitalize on an anticipated increase in the stock price of a technology company, TechCorp Inc. The investor believes that TechCorp’s upcoming product launch will drive significant market demand and propel the stock price higher. To implement their strategy, the investor decides to purchase call options on TechCorp stock.

The investor selects at the money (ATM) call options on TechCorp stock with a strike price of $150 and an expiration date three months in the future. The chosen options contract represents the right to buy 100 shares of TechCorp stock at $150 per share until the expiration date. The investor reviews the options chain and evaluates the premiums for the selected call options. Suppose the premium for the chosen call option is $10 per share, equating to a total premium of $1,000 (10 x 100 shares). This premium represents the cost of purchasing the call options.

Considering the potential upside potential and limited risk inherent in options trading, the investor decides to purchase one call option contract on TechCorp stock, investing $1,000 in premiums. The investor places a buy order for one call option contract on TechCorp stock at the prevailing market price of $10 per share. The options trade is executed, and the investor becomes the holder of the call option contract. Following the execution of the options trade, the investor closely monitors market developments, TechCorp’s stock price movements, and any relevant news or announcements related to the company’s product launch. The investor sets profit targets and stop-loss levels to manage risk and optimize potential returns.

Positive Scenario: Suppose TechCorp’s stock price experiences a significant increase following the product launch and reaches $170 per share before the options expiration date. In this case, the call options purchased by the investor will increase in value. The investor decides to exercise the options, buying TechCorp stock at the predetermined strike price of $150 per share.

Profit Calculation:

- Market Price of TechCorp Stock: $170 per share

- Strike Price of Call Option: $150 per share

- Premium Paid for Call Option: $10 per share

Profit per Share = Market Price of TechCorp Stock – Strike Price of Call Option – Premium Paid for Call Option Profit per Share = $170 – $150 – $10 = $10

Total Profit = Profit per Share x Number of Shares Total Profit = $10 x 100 = $1,000

Therefore, the investor realizes a total profit of $1,000 from exercising the call option contract.

Negative Scenario: Conversely, if TechCorp’s stock price fails to rise or declines below the strike price of $150 before the options expiration date, the call options purchased by the investor may expire worthless. In this scenario, the investor’s maximum loss is limited to the premium paid ($1,000) for the options contract, representing the total investment in the trade.

Option Strategies

- Covered Calls: Investors sell call options against existing long positions in the underlying asset to generate income from premium collection while limiting upside potential.

- Protective Puts: Investors purchase put options to hedge against potential downside risk in their underlying holdings, providing insurance against adverse price movements.

- Spreads: Option spreads involve the simultaneous buying and selling of multiple options contracts to capitalize on pricing differentials and volatility expectations.

- Straddles and Strangles: These strategies involve buying both call and put options with the same expiration date and strike price (straddles) or different strike prices (strangles) to profit from significant price movements in either direction.

Options pricing is influenced by various factors, including the underlying asset’s price, volatility, time to expiration, interest rates, and dividends. The Black-Scholes model and the binomial model are commonly used to calculate the theoretical value of options based on these factors.

Swaps are derivative contracts between two parties to exchange cash flows or other financial instruments based on predetermined conditions.

#3. Swaps

Swaps are derivative contracts between two parties to exchange cash flows or other financial instruments based on predetermined conditions. Swaps are highly customizable and serve diverse purposes, including managing interest rate risk, currency risk, credit risk (default swap), and commodity price risk

Common Types of Swaps

Interest Rate Swaps: Interest rate swaps involve the exchange of fixed-rate and floating-rate interest payments, allowing counterparties to manage their exposure to interest rate fluctuations.

Currency Swaps: Currency swaps entail the exchange of cash flows denominated in different currencies, enabling parties to hedge foreign exchange risk or access funding in foreign markets.

Commodity Swaps: Commodity swaps involve the exchange of cash flows based on the price movements of underlying commodities, allowing producers and consumers to hedge against commodity price volatility.

Swaps are traded over-the-counter (OTC), customized to meet the specific needs and preferences of counterparties. Unlike exchange-traded derivatives, swaps are not subject to standardized contract terms or centralized clearing, requiring counterparties to negotiate and document the terms of the swap agreement directly.

Unlike futures contracts, forwards are traded over-the-counter (OTC), allowing counterparties to tailor contract terms to their specific requirements.

#4. Forwards

Forwards contracts are customized agreements between two parties to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specified price (the forward price) on a predetermined future date. Unlike futures contracts, forwards are traded over-the-counter (OTC), allowing counterparties to tailor contract terms to their specific requirements.

Characteristics of Forwards

- Customization: Forwards can be tailored to meet the unique needs of counterparties, including the selection of underlying assets, contract sizes, expiration dates, and settlement terms.

- Flexibility: Forwards offer greater flexibility compared to standardized futures contracts, enabling counterparties to negotiate terms that best align with their risk management objectives and market expectations.

- Credit Risk: Since forwards are traded OTC, counterparties are exposed to credit risk—the risk that one party may default on its contractual obligations. Counterparty credit assessments and collateral agreements are commonly used to mitigate credit risk in forward transactions.

Forwards are widely used in various markets, including foreign exchange, commodities, and over-the-counter derivatives. Hedgers and investors utilize forwards to manage price risk, gain exposure to specific assets or markets, and structure customized investment and trading strategies.

Regulation of Derivatives and Oversight

Derivatives markets are subject to regulatory oversight by government agencies and self-regulatory organizations to ensure market integrity, transparency, and investor protection. Key regulatory bodies overseeing derivatives markets include:

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States

- Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) in the United States

- European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) in the European Union

- Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the United Kingdom

- International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) globally

Regulatory reforms following the 2008 financial crisis, such as the Dodd-Frank Act in the United States and the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) in the European Union, have aimed to enhance transparency, reduce systemic risk, and improve oversight of derivatives markets.

Risks Associated with Derivatives

- Market Risk: This is the primary concern, referring to losses due to price fluctuations of the underlying asset (stocks, bonds, currencies) on which the derivative is based. If the underlying asset moves against your expectation, you could suffer significant losses.

- Counterparty Risk: This risk arises from the possibility that the other party to your derivative contract defaults on their obligations. This is more prevalent in over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, which are less regulated than exchange-traded ones.

- Liquidity Risk: Unlike exchange-traded derivatives with high liquidity, some OTC derivatives might be difficult to enter or exit quickly at a fair price. This can amplify losses if you urgently need to unwind your position.

- Leverage: Derivatives often involve leverage, which magnifies both potential gains and losses. A small price movement can lead to a disproportionately large outcome in your favor or against you.

Here’s a quick comparison between derivatives and traditional investments:

| Derivatives | Traditional Investments (Stocks/Bonds) | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk | Generally Higher | Generally Lower |

| Complexity | Higher | Lower |

| Potential Returns | Higher or Lower | Moderate Returns |

Criticisms and Controversies

Derivatives have faced criticism and controversy due to their role in financial crises, market manipulation, and speculative excesses. Critics argue that derivatives can amplify systemic risk, encourage reckless behavior, and contribute to market instability. Key criticisms of derivatives include:

- Lack of Transparency: Some derivatives markets lack transparency, making it difficult for regulators, investors, and the public to assess the true risks and exposures of market participants.

- Complexity and Opacity: Derivatives can be highly complex instruments with opaque pricing and valuation methods, posing challenges for investors to understand and assess their risks.

- Too Big to Fail: The concentration of derivatives trading among a few large financial institutions has raised concerns about systemic risk and the potential for taxpayer-funded bailouts in the event of a market crisis.

- Regulatory Arbitrage: Financial institutions may engage in regulatory arbitrage by structuring derivatives transactions to circumvent regulatory requirements, undermining the effectiveness of oversight and risk management measures.

Future Trends and Developments

Despite the criticisms and controversies surrounding derivatives, the demand for these financial instruments continues to grow, driven by technological advancements, globalization, and evolving market dynamics. Key trends and developments shaping the future of derivatives markets include:

- Innovation in Product Design: Financial engineers and market participants are continuously innovating new derivative products and strategies to meet evolving investor needs and market conditions, including ESG derivatives, cryptocurrency derivatives, and decentralized finance (DeFi) derivatives.

- Electronic Trading and Automation: The shift towards electronic trading platforms and algorithmic trading has transformed derivatives markets, increasing efficiency, liquidity, and accessibility while reducing trading costs and execution times.

- Regulatory Reforms: Regulators continue to implement reforms aimed at enhancing transparency, resilience, and integrity in derivatives markets, including the adoption of central clearing, trade reporting, and margin requirements for OTC derivatives.

- Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Financial firms are increasingly leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies to analyze market data, develop trading strategies, and optimize risk management processes in derivatives markets.

- Expansion of Cryptocurrency Derivatives: The growing popularity of cryptocurrencies has led to the emergence of cryptocurrency derivatives markets, offering investors exposure to digital assets through futures, options, swaps, and other derivative products.

Conclusion

Derivatives are complex financial instruments that play a vital role in modern finance, providing investors with opportunities for risk management, speculation, and portfolio diversification. While derivatives offer various benefits, they also entail risks and challenges that require careful consideration and risk management. By understanding the mechanics, uses, and risks associated with derivatives, investors can make informed decisions and effectively navigate derivatives markets in pursuit of their financial goals.

Share on Social Media: